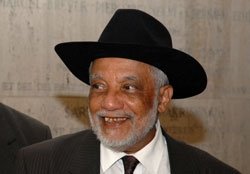

René Depestre is a Haitian writer, the author notably of the award-winning “Hadriana dans tous mes rêves” (“Hadriana in All My Dreams”). He was present at the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists organized in Paris. He was also participating in the commemoration of its 50th anniversary. He looks back on the historical 1956 event.

René Depestre is a Haitian writer, the author notably of the award-winning “Hadriana dans tous mes rêves” (“Hadriana in All My Dreams”). He was present at the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists organized in Paris. He was also participating in the commemoration of its 50th anniversary. He looks back on the historical 1956 event. The First Congress was held at a time when African countries were still colonies. What did it represent for you?

First of all, an extraordinary opportunity. It allowed me to encounter and know the ideas of intellectuals I hadn’t heard of. It allowed me to better understand the diversity of black experience in relation to slavery and colonization, and to realize that the various historical journeys of Africa and its Diaspora didn’t always match. In my case, I had a particular experience. Dictatorships in Haiti made it such that “my adversary” wasn’t a white man, he was a Haitian, like me. I didn’t entirely agree with the tenets of Negritude, because I was afraid it would end up as a form of essentialism, totalitarianism or fundamentalism. At the same time I was confident, because I knew that men like Léopold Sédar Senghor and Alioune Diop from Senegal and the Martiniquais Aimé Césaire were engaging in a cultural struggle of decolonization.

Interview by Jasmina SopovaWhat is your perspective now on the First Congress?

It was the first gathering of its kind in the French-speaking world. “Présence Africaine”, the journal and the publishing house founded in Paris by Diop, Senghor, Césaire, were the pioneers that swept my generation into the movement. This Congress, held at the Sorbonne, cradle of European knowledge, restored our self-confidence. At the same time it showed the world a black intelligentsia existed. Beyond that the Congress produced a creative effervescence that found expression in historiography, anthropology, literature and poetry. All that work did not make racism disappear, but since 1956 we have been better prepared to stand up to it.

But for me colonization isn’t over. There has been decolonization of institutions, and of the relations between the old colonial empires and their African, Asian and American colonies. There has also been a certain decolonization of mentalities.

Yet there is a more subtle colonization that we should have achieved: it is the decolonization of semantics, at the level of words, starting with “black”, “white”, “yellow”. This means that 50 years after the Congress, young people, particularly in the suburbs, hang on to myths supposedly related to identity, based on skin colour. They form “black” associations. This phenomenon is a regression in relation to the progress made by the generation of Senghor and Césaire, mine and the one that followed.

What is the role today of the intelligentsia of Africa and the Diaspora?

Today it is not a question of affirming black cultures versus others. The colonial or racial question has been replaced by the issue of globalization. If the latter remains strictly financial, we are heading for disaster. To have ultramodern airports is not sufficient if we don’t have the Airbuses of the imagination to take off. What is cruelly lacking in globalization is “globality” – in other words the totality of the values of different civilizations. All civilizations are concerned. Some panic and fall into fundamentalism. Others make the transition with much greater ease and joie de vivre. Some have bigger obstructions, like Africa, like Haiti. Globalization should also provide the opportunity to raise the level of solidarity in the world for those who have been left behind.

Photo: © UNESCO/ M. Ravassard